I wanted to post Part III of my look at run distributions today but it looks it will be over the weekend. In other news...

Cubs tickets went on sale today. I get decent tickets for a Phillies game in August. Third row in section 215 at $46 a ticket (and that's not including then "convenience" charge). But no folks, they could not afford an extra $3m a year for 3 years to sign Furcal.

Anyway, I specifically looked for Phillies tickets to see Aaron Rowand. I hope Aaron does well for the Phillies this year and it will be nice to actually have a team in the NL to roof for.

Friday, February 24, 2006

Friday, February 17, 2006

Run Distribution Part II: Sox v. Indians (Offense)

So how does Cleveland score more runs than the Sox, allow less runs than the Sox, and finish 6 games back?

Actual Records

Pythagorean Records

I've found that run distribution is part of the reason for this discrepancy. As you can see, runs scored accounted for the biggest difference in the pythagorean standings as the two teams gave up an almost identical amount of runs. The Cleveland offense, however, scored 49 more runs, and isolating this component adds 4.55 wins to their pythagorean record.

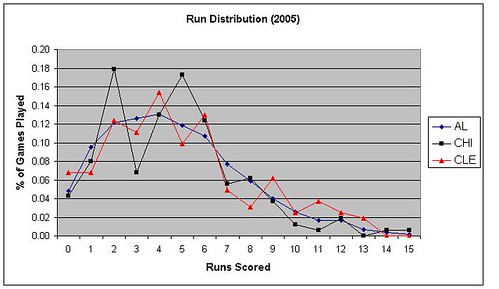

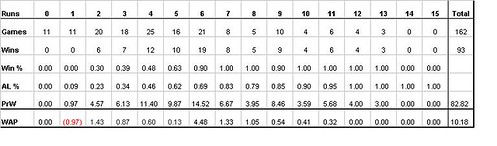

There is nothing that looks extraordinary in this graph. Both teams played a similar amount of games where the offense scored 4 runs or less. Cleveland actually had more of these games, 85 to Chicago's 81. Neither team differed that much from the AL average in these games. Still, it's surprising Cleveland wasn’t able to score runs on a more consistent basis.

On the flip side, you can also see how many high scoring games the Cleveland offense achieved. They had 27 games of at least 9 runs scored compared to only 20 for the Sox.

As we saw in Part I, concentrating runs in a bunch of high scoring games is not an optimal distribution pattern. They do add to your winning percentage, but each run scored is worth marginally less as your run total increases. For example, going from three runs scored to six runs scored last year would have more than doubled your expected winning percentage from .340 to .691, a difference of .351. Going from six runs scored to nine brought you to .846, only a difference of .155.

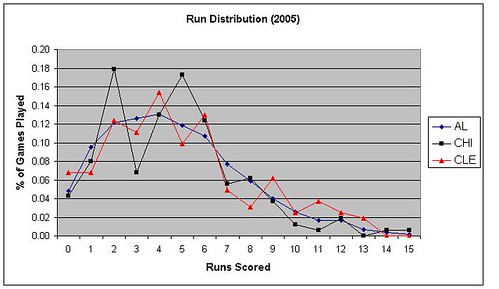

Predicted Wins

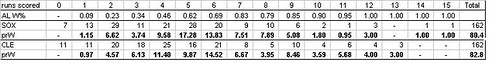

The chart below gives the distribution of runs scored for the Sox and Indians last year as well as the average winning percentages for AL teams at each run level. From these numbers, you can calculate the amount of Predicted Wins (prW) each offense would have if they received league average pitching.

As you can see, the Sox offense racks up 80.4 wins while Cleveland comes in 82.8, a difference of 2.4 games. This is 2.1 games less than the 4.5 game difference derived from the pythagorean record.

There is one huge caveat when looking at the offense in this manner: they are not including park effects! As we know, the Cell is a hitter's park, and the Jake has become a pitcher's park. This means that a run in the Jake is worth more in terms of winning percentage than a run in the Cell. And it also means the 2.4 prW gap may actually be something closer to the 4.5 pythagorean difference when park effects are included. Of course, the same will be true for runs allowed when we take a look at pitching and defense in Part III.

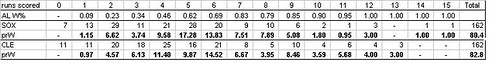

Actual Winning Percentage

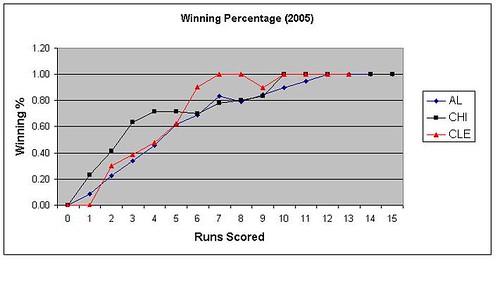

So Predicted Wins doesn’t get us too far when we factor in park effects. That’s fine as I think each teams actual win percentages are much more interesting. Unfortunately, I’m not quite sure what, if any, conclusions to draw from them.

The Sox were much better than league average in low and medium scoring games while Cleveland beat the league average in high scoring games.

The table above breaks down these games into the three categories. The odd thing about this breakdown is that both pitching staffs gave up nearly the same amount of runs but with very different results. The Cleveland staff actually gave up less runs than the Sox so there is no obvious reason why they would do worse in low scoring games.

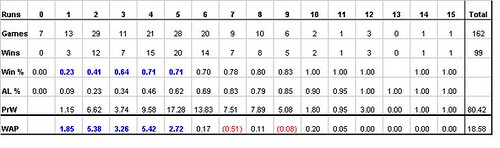

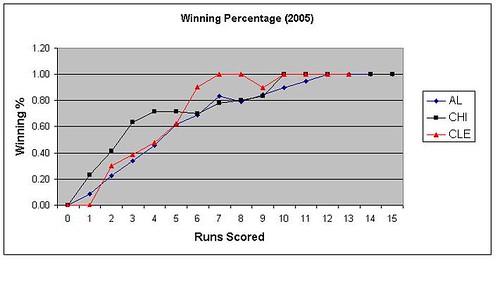

The two tables below calculate a number called WAP (Wins Above Predicted). This number shows how many wins each team recorded above the prW number previously calculated.

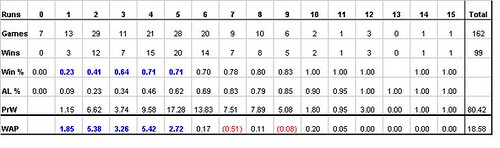

Sox WAP

The Sox has an unbelievable record in games where they scored 5 runs or less. They went 57-42 for a winning percentage of .523. The league average winning percentage for these games would have been .350 and only 38 wins. The Sox WAP of 18.6 comes almost entirely from games where the Sox scored 5 runs or less.

I'm almost suprised that the Sox didn't figure out a way to win a game in which the offense scored no runs at all. They were able to attain a winning record by just scoring three runs while the average AL teams had to score five. They even had a not to shabby winning percenetage of .410 in games where they scored two runs.

I would have to attribute this to dominant pitching, superior game strategy, and a good amount of luck. There is just no way you can expect to produce so many wins in these games without some luck on your side unless you have five Johan Santanas taking the mound for you. The Sox may have had the best rotation in baseball, but they weren’t that dominant.

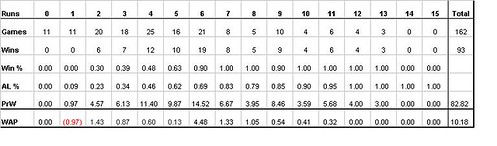

Cleveland WAP

The Indians don't exactly do badly in low scoring games, as they come in just above league average. Going back to those 85 games of 4 runs or less scored by the Indians, they were actually about 2 games better than league average at 25-60. But that record is less than stellar when compared to the Sox, who played four less games at that level, but finished with 12 more wins at 37-44.

At the high end, Cleveland was absolutely dominant in games when they scored at least six runs. They were 58-3 for winning percentage of .951. League average for these games would have been 50-11 for an .820 winning percentage. The Sox finished these games at 42-11, approximately league average.

I have some theories on how these results occured, but I plan on holding off trying to explain them until after I look at the runs allowed distribution in Part III.

Actual Records

| Team | W | L | GB |

| Sox | 99 | 63 | - |

| CLE | 93 | 69 | 6 |

Pythagorean Records

| Team | RS | RA | W | L | GB |

| CLE | 790 | 642 | 96 | 66 | - |

| Sox | 741 | 645 | 91 | 71 | 5 |

I've found that run distribution is part of the reason for this discrepancy. As you can see, runs scored accounted for the biggest difference in the pythagorean standings as the two teams gave up an almost identical amount of runs. The Cleveland offense, however, scored 49 more runs, and isolating this component adds 4.55 wins to their pythagorean record.

There is nothing that looks extraordinary in this graph. Both teams played a similar amount of games where the offense scored 4 runs or less. Cleveland actually had more of these games, 85 to Chicago's 81. Neither team differed that much from the AL average in these games. Still, it's surprising Cleveland wasn’t able to score runs on a more consistent basis.

On the flip side, you can also see how many high scoring games the Cleveland offense achieved. They had 27 games of at least 9 runs scored compared to only 20 for the Sox.

As we saw in Part I, concentrating runs in a bunch of high scoring games is not an optimal distribution pattern. They do add to your winning percentage, but each run scored is worth marginally less as your run total increases. For example, going from three runs scored to six runs scored last year would have more than doubled your expected winning percentage from .340 to .691, a difference of .351. Going from six runs scored to nine brought you to .846, only a difference of .155.

Predicted Wins

The chart below gives the distribution of runs scored for the Sox and Indians last year as well as the average winning percentages for AL teams at each run level. From these numbers, you can calculate the amount of Predicted Wins (prW) each offense would have if they received league average pitching.

As you can see, the Sox offense racks up 80.4 wins while Cleveland comes in 82.8, a difference of 2.4 games. This is 2.1 games less than the 4.5 game difference derived from the pythagorean record.

There is one huge caveat when looking at the offense in this manner: they are not including park effects! As we know, the Cell is a hitter's park, and the Jake has become a pitcher's park. This means that a run in the Jake is worth more in terms of winning percentage than a run in the Cell. And it also means the 2.4 prW gap may actually be something closer to the 4.5 pythagorean difference when park effects are included. Of course, the same will be true for runs allowed when we take a look at pitching and defense in Part III.

Actual Winning Percentage

So Predicted Wins doesn’t get us too far when we factor in park effects. That’s fine as I think each teams actual win percentages are much more interesting. Unfortunately, I’m not quite sure what, if any, conclusions to draw from them.

The Sox were much better than league average in low and medium scoring games while Cleveland beat the league average in high scoring games.

| runs | CHI | CLE | W+- |

| 0-2 | 15-34 | 6-36 | +9 |

| 3-5 | 42-18 | 29-30 | +13 |

| 6+ | 42-11 | 58-3 | -16 |

The table above breaks down these games into the three categories. The odd thing about this breakdown is that both pitching staffs gave up nearly the same amount of runs but with very different results. The Cleveland staff actually gave up less runs than the Sox so there is no obvious reason why they would do worse in low scoring games.

The two tables below calculate a number called WAP (Wins Above Predicted). This number shows how many wins each team recorded above the prW number previously calculated.

Sox WAP

The Sox has an unbelievable record in games where they scored 5 runs or less. They went 57-42 for a winning percentage of .523. The league average winning percentage for these games would have been .350 and only 38 wins. The Sox WAP of 18.6 comes almost entirely from games where the Sox scored 5 runs or less.

I'm almost suprised that the Sox didn't figure out a way to win a game in which the offense scored no runs at all. They were able to attain a winning record by just scoring three runs while the average AL teams had to score five. They even had a not to shabby winning percenetage of .410 in games where they scored two runs.

I would have to attribute this to dominant pitching, superior game strategy, and a good amount of luck. There is just no way you can expect to produce so many wins in these games without some luck on your side unless you have five Johan Santanas taking the mound for you. The Sox may have had the best rotation in baseball, but they weren’t that dominant.

Cleveland WAP

The Indians don't exactly do badly in low scoring games, as they come in just above league average. Going back to those 85 games of 4 runs or less scored by the Indians, they were actually about 2 games better than league average at 25-60. But that record is less than stellar when compared to the Sox, who played four less games at that level, but finished with 12 more wins at 37-44.

At the high end, Cleveland was absolutely dominant in games when they scored at least six runs. They were 58-3 for winning percentage of .951. League average for these games would have been 50-11 for an .820 winning percentage. The Sox finished these games at 42-11, approximately league average.

I have some theories on how these results occured, but I plan on holding off trying to explain them until after I look at the runs allowed distribution in Part III.

Friday, February 10, 2006

Run Distribution Part I: The New Sox

It's well known that White Sox outplayed their expected Pythagorean record from anywhere from 7 to 10 games, depending on which system you use. Now many people chalk this up to "luck" and some people go as far to judge a team not by the amount of games they actually win but by their run differential alone - as if run differential represented some intrinsic value of a baseball team.

It's actually quite ironic that people who pride themselves on taking a scientific view of the game would describe something that they aren't able explain as "luck". That may be a bit unfair, as the majority of bloggers realize that while luck plays a part, other factors, such as managerial decisions and run distribution, also play an important role. But too many times people write-off the variance between a team's actual record and pythagorean record as luck without making any effort to look for other possible explanations.

Pythagorean won/loss records are certainly a great, if blunt, tool in evaluating baseball teams. Anyone who looked at the NL East standings at the 2005 All-Star break would have realized that the Washington Nationals were going to have a difficult time staying in first place. While they were 16 games over 500 they had allowed more runs than they had scored, 361 to 357. No amount of managerial skill or run distribution could explain a difference that large and luck (along with a solid closer) certainly played a major role in their first half success.

Of course, the other surprise team in baseball at the break was the White Sox, and while they were already outplaying their pythagoreanan record by 7 games, they still had the best pythagorean winning percentage (.587)in the American League at the break.

This was actually a nice change a pace for the Sox as they had fallen short of thier pythagorean projections for the previous three seasons. And of course I couldn't help but wonder if the change was due to Kenny Williams offseason emphasis on smallball and defense. To do this I wanted to take a closer look at their run distribution in 2005 compared the 2004 White Sox squad.

The Same, But Different

Before I begin, I guess I should state what I define as "smallball". On offense, I would simply define it as sacrificing outs for runs. This will reduce your chance of a big inning but increase your chance of scoring at least one run. So yes, the Sox still played "longball" and hit 200 home runs for the sixth straight year. But they also employed a strategy of bunting, stealing, and moving runners over that emphasized getting one run across the plate.

Over at Beyond the Boxscore, Cyril Morong recently did his own comparison between the offense in 2005 and 2004, but came away unimpressed with the changes that were made. While I think he does a great job of presenting the facts, I don't think he came up with the right conclusions.

There's no denying the fact that the 2005 White Sox scored 124 less runs than the 2004 version and this certainly wasn't what Kenny Williams had in mind as he changed the team in the offseason. Unfortunately for Williams, players such as Uribe, Crede, Rowand and Pierzynski, did not have the offensive years that were expected of them.

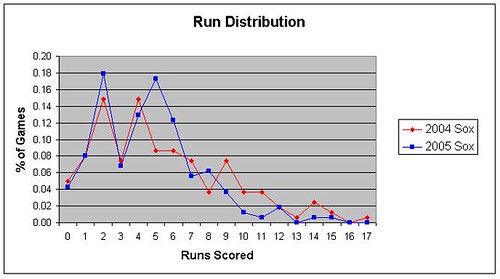

Morong then looks at run distribution to see if the 2005 version was better than the 2004 version at avoiding low scoring games, and he says no, they weren't any better. They actually played the same amount of low scoring games. Both teams played 81 games where they scored 4 runs or less and 81 games where they scored 5 runs or more.

While Morong sees this information as evidence that the Sox weren't able to build a more consistent offense, I can't help but find it remarkable. Do you mean to tell me that the Sox offense sacrificed 124 runs in the offseason and still managed to score at least 5 runs in a game as many times as the 2004 team? That's quite amazing. And when you add in the fact that American League teams scored less runs overall in 2005 (4.74 per game compared to 5.01) you can emphatically say yes, the 2005 White Sox did do a better job of avoiding the low scoring game.

As you can see from the distribution chart, the 2004 White Sox did not have an offensive advantage over the 2005 team until you get to 9 runs scored. The 2004 team just happened to score double digits in a ridiculous amount of games. That had the effect of driving up their pythagorean winning percentage but did little to add actual wins. A team will win over 80% of the games they play when they score at least 7 runs. So it doesn't make much of a difference in the win column whether the offense scores 10 runs or 15 runs in one particular game. The bottom line is that those 124 extra runs that were scored by the 2004 team did not help the Sox win many more ballgames.

In 2005, the Sox were basically able to upgrade defensively at left, shortstop, and rightfield without really giving up much, if anything, in offense. Indeed, if a few more players had lived up to their offensive expectations, the Sox very well may have pulled off an impressive feat of improving their offense while scoring less runs. All hail Kenny Williams.

In Parts II and III, I plan on comparing the 2005 White Sox runs scored and a runs allowed distributions to those of the Cleveland Indians. The Indians finished with the best pythagorean record in the AL (5 games ahead of the Sox) yet finished 6 games behind the Sox in the standings. I'm hoping the distributions will shed a little bit of light on how this result occured.

UPDATE:

In response to a comment below, I thought it would be a good idea to try and quantify the difference in the offense.

First, you can get an expected number of wins by an offense by comparing their run distribution to the league average winning percentage at each run scoring level. For example, in 2005, a team that scored 5 runs won 61.7% of their games. If you go through the run distribution for the 2005 Sox (and I do this in upcoming posts) their offense should have produced 80.4 wins when combined with league average pitching. If you plugged the 2004 Sox into the same distribution chart, they would have been expected to win 87 games.

However, more runs were scored in 2004 and the winning percentage for each distribution level would be lower. Therefore the 2004 Sox expected offensive win total would drop to 85 or 86. You would need the winning percentages for each scoring level in 2004 to get the exact number and I don't have those readily available. However, I think the above exercise gets close enough to the truth of the matter which is that 2004 offense was better, but not as much as the runs scored gap suggests.

It's actually quite ironic that people who pride themselves on taking a scientific view of the game would describe something that they aren't able explain as "luck". That may be a bit unfair, as the majority of bloggers realize that while luck plays a part, other factors, such as managerial decisions and run distribution, also play an important role. But too many times people write-off the variance between a team's actual record and pythagorean record as luck without making any effort to look for other possible explanations.

Pythagorean won/loss records are certainly a great, if blunt, tool in evaluating baseball teams. Anyone who looked at the NL East standings at the 2005 All-Star break would have realized that the Washington Nationals were going to have a difficult time staying in first place. While they were 16 games over 500 they had allowed more runs than they had scored, 361 to 357. No amount of managerial skill or run distribution could explain a difference that large and luck (along with a solid closer) certainly played a major role in their first half success.

Of course, the other surprise team in baseball at the break was the White Sox, and while they were already outplaying their pythagoreanan record by 7 games, they still had the best pythagorean winning percentage (.587)in the American League at the break.

This was actually a nice change a pace for the Sox as they had fallen short of thier pythagorean projections for the previous three seasons. And of course I couldn't help but wonder if the change was due to Kenny Williams offseason emphasis on smallball and defense. To do this I wanted to take a closer look at their run distribution in 2005 compared the 2004 White Sox squad.

The Same, But Different

Before I begin, I guess I should state what I define as "smallball". On offense, I would simply define it as sacrificing outs for runs. This will reduce your chance of a big inning but increase your chance of scoring at least one run. So yes, the Sox still played "longball" and hit 200 home runs for the sixth straight year. But they also employed a strategy of bunting, stealing, and moving runners over that emphasized getting one run across the plate.

Over at Beyond the Boxscore, Cyril Morong recently did his own comparison between the offense in 2005 and 2004, but came away unimpressed with the changes that were made. While I think he does a great job of presenting the facts, I don't think he came up with the right conclusions.

There's no denying the fact that the 2005 White Sox scored 124 less runs than the 2004 version and this certainly wasn't what Kenny Williams had in mind as he changed the team in the offseason. Unfortunately for Williams, players such as Uribe, Crede, Rowand and Pierzynski, did not have the offensive years that were expected of them.

Morong then looks at run distribution to see if the 2005 version was better than the 2004 version at avoiding low scoring games, and he says no, they weren't any better. They actually played the same amount of low scoring games. Both teams played 81 games where they scored 4 runs or less and 81 games where they scored 5 runs or more.

While Morong sees this information as evidence that the Sox weren't able to build a more consistent offense, I can't help but find it remarkable. Do you mean to tell me that the Sox offense sacrificed 124 runs in the offseason and still managed to score at least 5 runs in a game as many times as the 2004 team? That's quite amazing. And when you add in the fact that American League teams scored less runs overall in 2005 (4.74 per game compared to 5.01) you can emphatically say yes, the 2005 White Sox did do a better job of avoiding the low scoring game.

As you can see from the distribution chart, the 2004 White Sox did not have an offensive advantage over the 2005 team until you get to 9 runs scored. The 2004 team just happened to score double digits in a ridiculous amount of games. That had the effect of driving up their pythagorean winning percentage but did little to add actual wins. A team will win over 80% of the games they play when they score at least 7 runs. So it doesn't make much of a difference in the win column whether the offense scores 10 runs or 15 runs in one particular game. The bottom line is that those 124 extra runs that were scored by the 2004 team did not help the Sox win many more ballgames.

In 2005, the Sox were basically able to upgrade defensively at left, shortstop, and rightfield without really giving up much, if anything, in offense. Indeed, if a few more players had lived up to their offensive expectations, the Sox very well may have pulled off an impressive feat of improving their offense while scoring less runs. All hail Kenny Williams.

In Parts II and III, I plan on comparing the 2005 White Sox runs scored and a runs allowed distributions to those of the Cleveland Indians. The Indians finished with the best pythagorean record in the AL (5 games ahead of the Sox) yet finished 6 games behind the Sox in the standings. I'm hoping the distributions will shed a little bit of light on how this result occured.

UPDATE:

In response to a comment below, I thought it would be a good idea to try and quantify the difference in the offense.

First, you can get an expected number of wins by an offense by comparing their run distribution to the league average winning percentage at each run scoring level. For example, in 2005, a team that scored 5 runs won 61.7% of their games. If you go through the run distribution for the 2005 Sox (and I do this in upcoming posts) their offense should have produced 80.4 wins when combined with league average pitching. If you plugged the 2004 Sox into the same distribution chart, they would have been expected to win 87 games.

However, more runs were scored in 2004 and the winning percentage for each distribution level would be lower. Therefore the 2004 Sox expected offensive win total would drop to 85 or 86. You would need the winning percentages for each scoring level in 2004 to get the exact number and I don't have those readily available. However, I think the above exercise gets close enough to the truth of the matter which is that 2004 offense was better, but not as much as the runs scored gap suggests.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

An E-mail Making the Rounds...

2006 Chicago Cubs Promotional Schedule

April 7: Home Opener and raising of the "Attendance Flag" to commemorate the magical 2005 season in which the Cubs were a bigger draw than any of their hated rivals. Not being raised: World Series Champions flag.

April 8: Presentation of the "Nice Neighborhood" rings to members of the 2005 squad in commemoration of their capturing of the city's heart by playing in such a cute little part of town. Not being presented: World Series Champions rings.

April 9: Home Opener Weekend festivities conclude with the Cardinals completing a sweep of the Cubs at Wrigley.

April 24: Win a Mark Prior autographed picture! 100 lucky fans will receive a 5 x 7" photo signed by the Cubs' 11-game winner!

April 25: Turn Back the Clock I with throwback jerseys, old-time music and special guests and relive the magic of the Cubs' epic loss to the Florida Marlins in the 2003 NLCS.

May 13: Turn Back the Clock II with authentic 1984 uniforms jerseys and an even more authentic loss to the 1984 NLCS champion San Diego Padres.

May 14: Precious Moments figurine doll to the first 10,000 female fans*.

June 15: Kerry Wood bobblehead day. The first 10,000 fans will receive a bobblehead doll of the Northsiders' all-time leader in simulated strikeouts!

June 16: Turn Back the Clock III - Kick off a rematch of the Cubs' most recent World Series appearance as they welcome the Detroit Tigers and try to beat them for the first time since 1945.

June 30: Cross-town Amnesty Day - All managers and first 25 players on the White Sox active roster will receive a complimentary win.

July 1: Turn Back the Clock IV - 1906 World Series rematch. Authentic memorabilia will be given out to lucky Cub fans, as will an authentic 1906-style massacre of their lovable losers.

July 2: Lovable Loser Day - First 15,000 losers get to fall in love with the Cubs even more as they are handed yet another staggering loss at home by yet another area team that has built something more substantial than their own ticket-scalping empire**.

July 14: Harry Caray Day, featuring an all-star tribute to the late and beloved former White Sox and Cardinals announcer.

August 1: Nine Games Back Day - First 10,000 fans in attendance to correctly explain what "Nine Games Back" means receive a Cubs t-shirt***.

August 19: Playoff Day. Come out and root for the Cubs as they stand on the brink of elimination against the Cardinals with forty-one games still left to play in the season. First 20,000 fans wearing Cubs gear receive a White Sox t-shirt.

September 2: Turn Back the Clock V - Cubs fans, come out and party like it's 1989 in this showdown against the 1989 NLCS champion San Francisco Giants!

October 1: Final Home Game / Wait 'Til Next Year Day - First 39,538 fans are idiots.

(*) This one's real, believe it or not. Precious Moments? Come on.

(**) Wrigley Field Premium Ticketing Services, 3717 N. Clark St.

(***) Contest runs through the end of the 2006 season. Okay, 2007 season.

April 7: Home Opener and raising of the "Attendance Flag" to commemorate the magical 2005 season in which the Cubs were a bigger draw than any of their hated rivals. Not being raised: World Series Champions flag.

April 8: Presentation of the "Nice Neighborhood" rings to members of the 2005 squad in commemoration of their capturing of the city's heart by playing in such a cute little part of town. Not being presented: World Series Champions rings.

April 9: Home Opener Weekend festivities conclude with the Cardinals completing a sweep of the Cubs at Wrigley.

April 24: Win a Mark Prior autographed picture! 100 lucky fans will receive a 5 x 7" photo signed by the Cubs' 11-game winner!

April 25: Turn Back the Clock I with throwback jerseys, old-time music and special guests and relive the magic of the Cubs' epic loss to the Florida Marlins in the 2003 NLCS.

May 13: Turn Back the Clock II with authentic 1984 uniforms jerseys and an even more authentic loss to the 1984 NLCS champion San Diego Padres.

May 14: Precious Moments figurine doll to the first 10,000 female fans*.

June 15: Kerry Wood bobblehead day. The first 10,000 fans will receive a bobblehead doll of the Northsiders' all-time leader in simulated strikeouts!

June 16: Turn Back the Clock III - Kick off a rematch of the Cubs' most recent World Series appearance as they welcome the Detroit Tigers and try to beat them for the first time since 1945.

June 30: Cross-town Amnesty Day - All managers and first 25 players on the White Sox active roster will receive a complimentary win.

July 1: Turn Back the Clock IV - 1906 World Series rematch. Authentic memorabilia will be given out to lucky Cub fans, as will an authentic 1906-style massacre of their lovable losers.

July 2: Lovable Loser Day - First 15,000 losers get to fall in love with the Cubs even more as they are handed yet another staggering loss at home by yet another area team that has built something more substantial than their own ticket-scalping empire**.

July 14: Harry Caray Day, featuring an all-star tribute to the late and beloved former White Sox and Cardinals announcer.

August 1: Nine Games Back Day - First 10,000 fans in attendance to correctly explain what "Nine Games Back" means receive a Cubs t-shirt***.

August 19: Playoff Day. Come out and root for the Cubs as they stand on the brink of elimination against the Cardinals with forty-one games still left to play in the season. First 20,000 fans wearing Cubs gear receive a White Sox t-shirt.

September 2: Turn Back the Clock V - Cubs fans, come out and party like it's 1989 in this showdown against the 1989 NLCS champion San Francisco Giants!

October 1: Final Home Game / Wait 'Til Next Year Day - First 39,538 fans are idiots.

(*) This one's real, believe it or not. Precious Moments? Come on.

(**) Wrigley Field Premium Ticketing Services, 3717 N. Clark St.

(***) Contest runs through the end of the 2006 season. Okay, 2007 season.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)